Investigation into the Effect of Monotonicity of Numerical Methods for the Heat Equation on Average Measured Temperature

Date:

1. Introduction

In this post, we investigate the physical impact of oscillations arising due to non-monotone schemes for the heat equation; see our discussion in On the Cause of Spurious Oscillations in Stable Numerical Methods for an in-depth analysis of the cause of oscillations. We return to the heat equation

\[\partial_t \left( c \theta \right) - \nabla \cdot \left(k \nabla \theta \right) = 0, \; \text{ in } \Omega,\]where $\Omega \subset \mathbb{R}^3$, and are interested in quantifying the discrepancies in measurable quantities, such as the average temperature over a subset of the boundary face.

We have already demonstrated in our previous post how implicit Euler Galerkin schemes using $P_1/Q_1$ elements violate the monotonicity condition of the solution, i.e., they do not preserve the positivity of the solution (and the initial bounds). Physically, we observe negative temperature values in the absence of any sink terms or negative Dirichlet boundary conditions. An in-depth analysis shows how the scheme becomes non-monotone, i.e., it does not preserve the positivity of the solution when the thermal conductivity or time step becomes too small. We also developed a scheme using appropriate quadrature that solves this issue and produces a monotone scheme, thereby eliminating the spurious oscillation causing negative temperature values.

1.1. Example setup

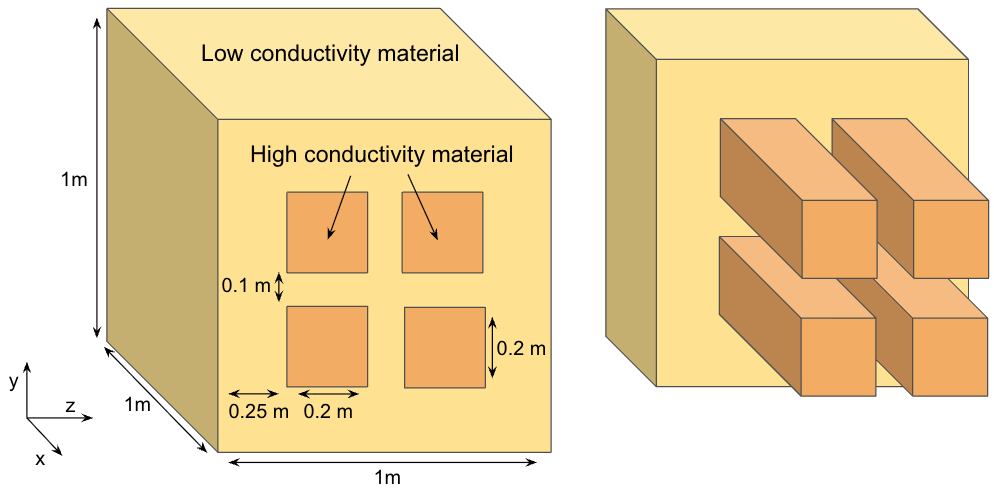

We now simulate a physical scenario to understand the effect of the negative temperature oscillations produced by the Gaussian quadrature compared to the inconsistency introduced by the trapezoidal quadrature. To this end, we consider a three-dimensional heterogeneous material occupying $\Omega = (0,1)^3$ as shown below.

The thermal conductivity and heat capacity for the two types of materials is $k_{high} = 1000$ [J/m $^\circ$ C s], $c_{high} = 10^6$ [J/m$^3$ s] and $k_{low} = 0.05$ [J/m $^\circ$ C s], $c_{low} = 10^6$ [J/m$^3$ s]. We consider Dirichlet boundary conditions on $\{ 0 \} \times (0,1) \times (0,1)$ where we set $\theta = 1$ [$^\circ$ C], and on the other faces we consider the Neumann no-flux boundary condition $\nabla \theta \cdot \nu = 0$.

2. Numerical Scheme and Solver

We consider first order implicit time stepping and spatial discretization using $Q_1$ bilinear elements. We consider two aproaches: (a) using the full quadrature when computing the mass matrix (Gaussian quadrature) and (b) using the trapezoidal rule to compute the mass matrix; see On the Cause of Spurious Oscillations in Stable Numerical Methods for complete details of the two approaches. We now know that approach (a) will lead to negative temperature values and (b) will preserve the positivity and bounds of the solution.

We develop and implement our scheme in deal.II 1. To efficiently handle the large scale of the problem, we parallelize our implementation using MPI and PETSc 2, the interface of which is offered in deal.II itself. As part of the linear solver, we consider the conjugate gradient (CG) method with the algebraic multigrid (AMG) preconditioner.

2.1. Measured Quantity

In order to compare the two approaches, we compute the temperature average on a subset of one of the boundaries

\[\label{eq:measured_value} \overline{\theta^n} = \frac{\int_{\Gamma_F} \theta^n_h d\Gamma }{\int_{\Gamma_F} 1 d\Gamma},\]where $\theta^n_h$ is the discretized solution obtained at time step $n$, and $\Gamma_F \subset \partial \Omega$ is a chosen subset. The motive for chosing \ref{eq:measured_value} is that it allows us to measure the temperature at one face of the heating object thereby mimicing actual physical measurements.

For our numerical results, we consider $\Gamma_F = \{ 1 \} \times (0.25, 0.75) \times (0.25, 0.75)$.

3. Results

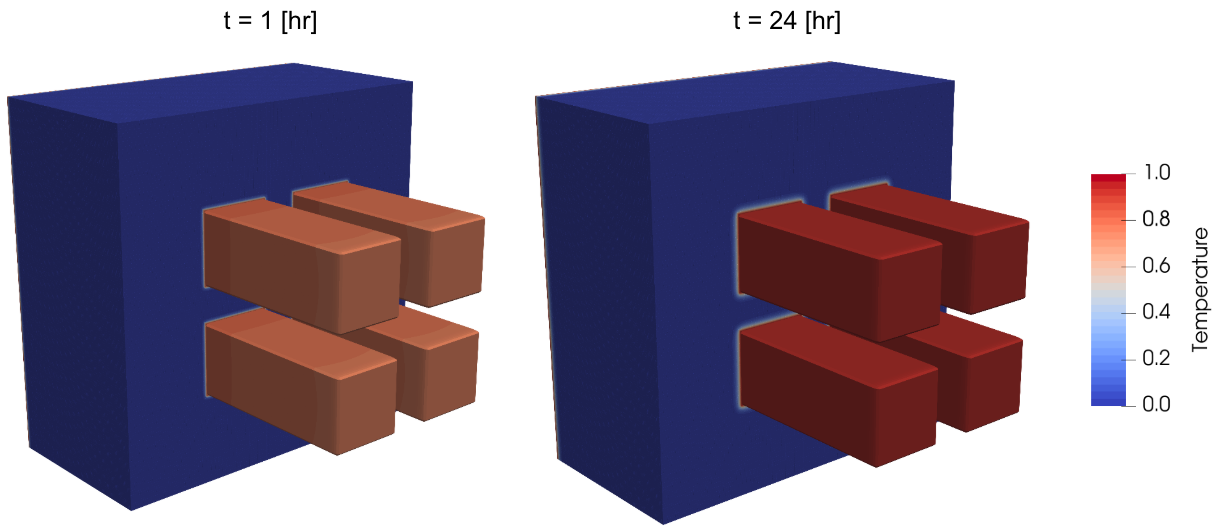

To compare our approaches (a) and (b), we first compute the reference solution using a really fine spatial mesh. We run the simulation over $(0, 24)$ [hr] using a time step of $\tau = 1$ [hr], and a uniform spatial mesh using edge length $0.00625$ [m] (corresponding to roughly 5 million degrees of freedom!). The simulation is launched on 10 processors, and the results at the first and last time steps are shown in Fig. 2.

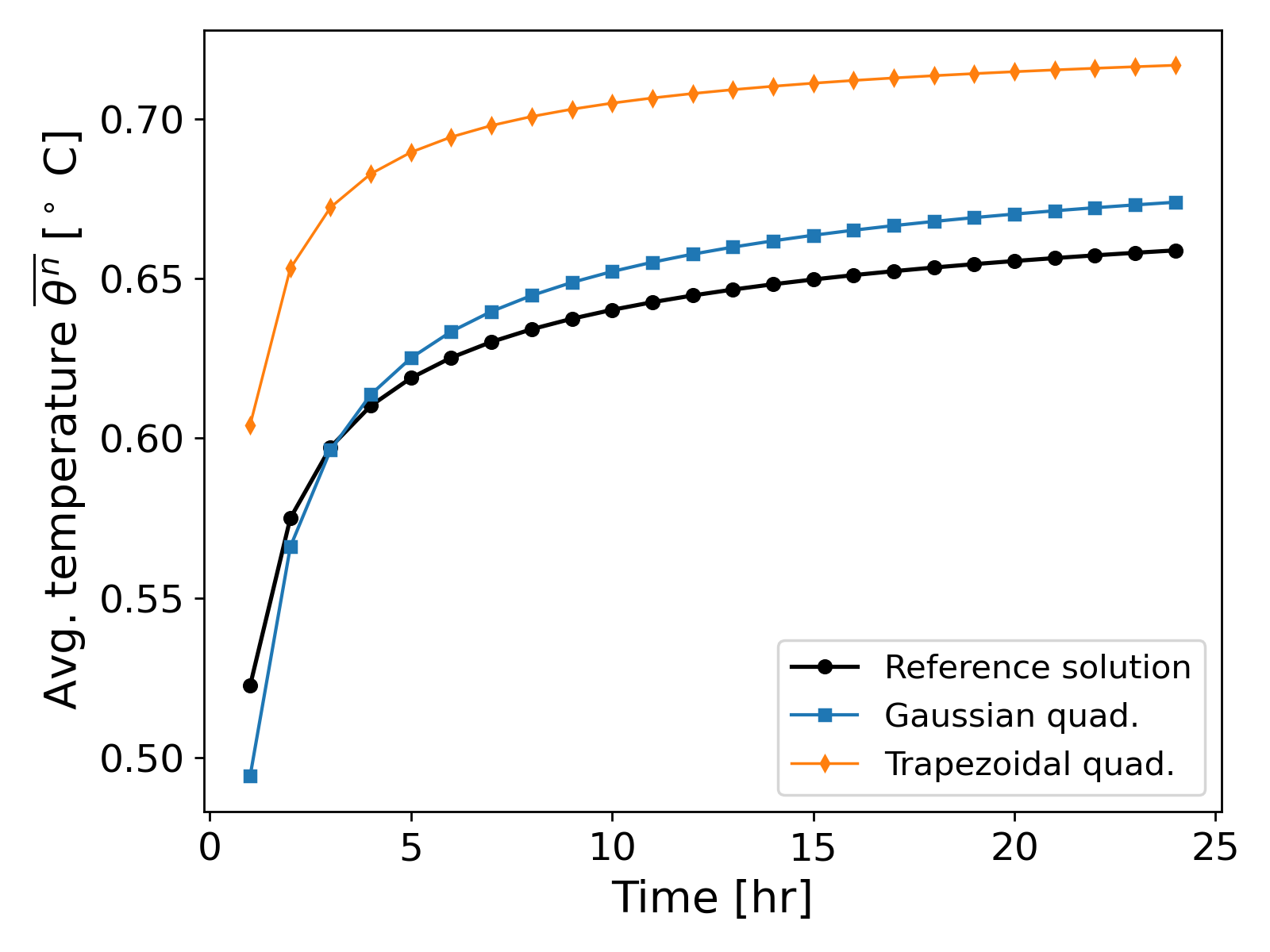

We now compute the solution using the Gaussian quadrature and trapezoidal quadrature on a uniform mesh with cell width $h = 0.025$ [m], and compute the average temperature given by \ref{eq:measured_value}. The results are shown in Fig. 3.

Discussion of results It can be observed from Fig. 3. that the Gaussian quadrature yields values closer to the reference solution than the trapezoidal quadature when using a coarse mesh, even though spurious oscillations (negative temperature values) are present when using the Gaussian quadrature. That is, even though the trapezoidal quadrature leads to positivity preserving scheme, the error introduced by the quadrature itself leads to large differences in the measured average temperature values.